Hi, folks. Happy 2023. It’s been a while. Januarys tend to be a bit chaotic over in my world.

You see, while most other folks got to unwind as December came to a close, my holiday season was just starting up. I alluded to this in my last post, so for those of you who have been waiting with bated breath for this topic: it’s here! Merry Christmas to you, once again!

Let’s start the season at the top, which doesn’t fall too far away from the Christmas date most of you are familiar with: December 19th. In Ukrainian Orthodox/Catholic tradition, this date marks the Feast of St. Nicholas (again, per the oft-cited “old calendar;” modern day celebrators commemorate him on December 6th). St. Nicholas is widely celebrated in the Ukrainian community- not just during the winter holiday season, but year-round. He’s seen as the patron saint of merchants, seafarers, and children. So, if you’re out there at home connecting the dots, Ukrainian children anticipate the arrival of jolly ol’ Saint Nick to kick off winter festivities- not Santa Claus.

(As an aside, I was recently rummaging through an old journal from my preschool years. An entry from my teacher around Christmastime read: “Dianna was unsure of how to react to Santa Claus. Not sure why she would have this reaction.” I had a good chuckle over that line.)

Part of the reason why St. Nicholas was offered sainthood was because of his charitable and life-saving actions for children. December 19th is believed to be the day he died, so what better way to commemorate the patron saint of protecting kids than by giving them some gifts ahead of Christmas?

(Photo: Marianne Hawryluk via Facebook)

There he is, back in action! Giving out gifts to all the good kids!

Of course, this is an actor portraying the Saint on or around his feast day. In the Ukrainian-American diaspora, we’d usually spend most of November and December preparing for our annual “St Nicholas Concert” in Ukrainian School (yes… that’s a very real thing). The gifts don’t show up just because you’re there and under the age of 18, though. Songs are sung, half-memorized poems are recited, there’s probably a skit or dance thrown in the mix for good measure. All in effort to bring out St Nicholas, his sleigh of presents, and his ranks of angel assistants.

Yes, folks. Even the kid who plays the Christmas tree gets a gift from St. Nick. By the way- we call that tree a yalynka. Not the kid playing the tree. We call him Tey. He’s my brother.

So you get your gift or two from St. Nick on December 19th. Your American friends wake up on the 25th and rip open everything in sight of their yalyn- I mean, Christmas tree. In our family, we opened presents on the 25th. We saw the 25th as “material Christmas”- not so much a spiritual thing, but something to have its own day of celebration than to encroach on the festivities that occur in early January. If you’re thinking to yourself: “Dianna, why would you cut out the best part of Christmas from Christmas?” well, ho, ho, ho, and buckle up, folks.

Per “the old calendar,” Christmas Eve falls on January 6th. Old tradition states that on Christmas Eve, the entire household must fast until the youngest member of the household spots the first star of the evening- signifying the Star of Bethlehem. Most people don’t follow the fasting part, but the star searching remains an integral part of the evening. It’s the only time of the year where I was not thrilled to be the oldest child.

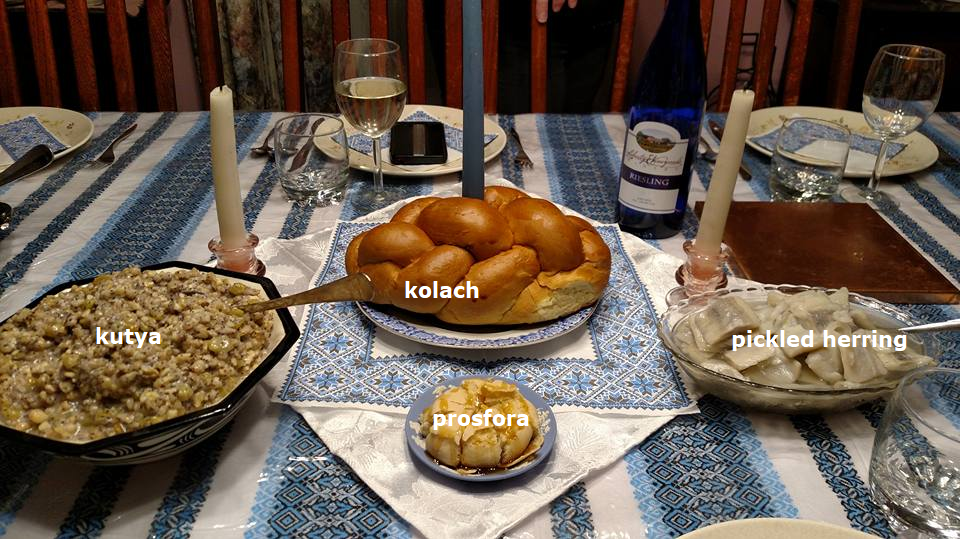

The Christmas Eve dinner- better known as Svyat Vechir, or “Holy Night,” requires some pre-Christianization-era prep work before the food even goes on the table. A sheaf of wheat, or didukh, is brought into the home to symbolize the spirits of family members past and future. The didukh remains in the home from Christmas Eve until the Feast of Jordan, where it’s symbolically burned to free the spirits until next year. In setting the table for the evening’s feast, a thin layer of hay is placed in the center to symbolize- you guessed it- the manger where Jesus was born. On top of the hay, a kolach- or circular braided bread- is placed. A candle is placed in the center of the bread and lit when the meal begins. I’ll let you take a wild guess what that represents.

If you guessed baby Jesus, you’re correct. Give yourself a high-five (though, in pre-Christian traditions, it also symbolizes family and its interwovenness with nature).

One more thing before we get into the food: at each corner of the table, underneath the cloth, a clove of garlic is placed to ward off evil spirits. Sometimes, after dinner, my brother would sneak the cloves out and eat them raw. Don’t ask him about his dating life during those times.

The star is spotted. The family gathers around the table in prayer. We’re about to embark on a 12-course vegetarian meal.

Yes, you read that correctly. Everything served at the evening’s feast is made without meat, dairy, or eggs.

There’s no real order that you’re supposed to eat the courses, but the first two must always be first. The prayer is followed by a koliadka, or carol, and the passing of the prosfora. The prosfora is a leavened bread topped with honey, which is divided among the members at the dinner table. It’s given out to the oldest person at the table first, then gets passed by age down to the youngest.

Next comes the kutya. Kutya is a mixture of boiled buckwheat, poppy seeds, and honey (some folks, like my grandmother, add raisins). Pre-Christianization, kutya was strictly prepared during the winter season as an offering to the gods for a bountiful harvest. Its effectiveness is put to the test as bowls are doled out across the table- the oldest member of the house takes their first spoonful and throws the kutya onto the ceiling. If it sticks, it’s going to be a plentiful and lucky year. If it doesn’t, you’re going to have some peeved dinner guests (and bad luck).

I just threw a whole lot of new words at you. Let’s review:

There will not be a test on this at the end of the blog.

As for the pickled herring- yes, fish is allowed at Svyat Vechir! I’ve seen a lot of varieties of fish on the dinner table over the years- from sprats (sardines coated in seasoning and olive oil) to jellied fish, to fried tilapia, whole trout, and salmon filets. Some options have certainly been better than others. The jellied fish still makes me shudder.

You also have some Ukrainian culinary staples that make the cut for Christmastime. Borscht (beet soup), varenyky (pierogies), and holubtsi (cabbage rolls stuffed with rice and mushrooms) are all integral for a Svyat Vechir meal. Kompot is often served as the evening’s beverage- it’s a fruit juice made with whatever fruit’s on hand. Pears, cherries, plums- it’s all fair game. My grandmother made a kompot with prunes one year, and I’ll let you draw your own conclusions about how the rest of that evening went.

Still have a hankering for some sweet stuff? Fear not. You can get your fill of makivnyk, or poppy seed cake, with some black coffee. Or maybe a fresh pampushok is more your speed- who doesn’t love a good jelly doughnut?

The evening continues with koliady- Christmas carols- and well-wishes for the new year (called a vinchannya). Some larger-scale dinners will often feature a troupe of koliadnyky, or carolers performing a vertep, or nativity-inspired performance. Here’s an example:

Verteps don’t typically feature things you’d expect at a live Nativity. Sure, you’ve got your shepherds, goats, and angels. The Three Wise Men show up for a vinchannya or three. The Devil is usually the Evil Character. There may be some nefarious guards or merchants involved. In between these characters duking out the forces of good and evil, more koliadky are sung. All is merry and bright when good triumphs over evil in the end (spoiler alert).

The whole evening makes Christmas Day seem pretty lame, in comparison. There’s a 3-hour long Mass (that all of the kids get to skip school for), and anyone who didn’t get to open presents can go home and tear apart gifts to their hearts content.

Everyone, that is. Except for the koliadnyky. We hope they opened their presents before Mass.

Pictured: koliadnyky with the star-shaped shopka, or Nativity scene.

The carolers’ role, from Christmas Day until the Feast of Jordan, is to make their way into as many Ukrainian homes as possible to spread good fortune and cheer for the New Year. My siblings and I were always part of the caroling troupe each year. We’d map out our routes in various Ukrainian-American communities, set up an order of songs and vinchannya to perform at each house, and schlep out after Mass on Christmas Day. A lot of the homes we visited were those of elderly immigrants who may not have been able to make it to Mass. There were a good amount of tears flowing during those performances. While we performed, our audience likely processed memories of childhoods or even early adulthoods where these koliadnyky were banned by the Communists. They’d give us gifts of money (always donated to local youth organizations), baked goods, or even a full meal in exchange for our show. Some homes even offer the adults homemade liquor. Those houses got some extra singing time.

While we’re here, let’s talk about Koliada. The season of Koliada is often seen as being held on the “opposite” time of year as Kupala, which celebrates the summer solstice. The tradition of going door-to-door and wishing good tidings in the New Year predates Christianity. Troupes of performers used to relegate one night a year- January 13th, or Shchedrij Vechir (Generous Evening)- to perform verteps. Instead of the story of the birth of Jesus, troupe members would perform a reenactment of the story of Malanka. Legend has it that Malanka is the daughter of Mother Earth, who is kidnapped by her evil uncle. A rescuer saves Malanka from being taken to the Underworld, and peace is restored once again. The story is seen as the “rescuing of spring” from the evils of winter. In Ukraine, these are still performed with masked troupes putting on elaborate performances of Malanka’s tale. In fact, the Ukrainian New Year’s celebration on January 14th (or the eve of the 13th) is often referred to as simply Malanka.

Any homes we didn’t get to carol at on Christmas or New Year’s, we’d save for the Feast of Jordan, or January 19th. In Christianized context, the Feast of Jordan celebrates the date Jesus was baptized in the Jordan River. Churches will often put on one last “Prosfora” meal- named after the bread and honey eaten at the beginning- complete with all the traditional Christmas foods and carols. They’ll even have one last vertep performance for the travelling troupe to end on a high note.

Special thanks to Maria at Vinok Collective and Christmas In Ukraine for supplementing some of the information in this post.